Program

Hugo Wolf (1860-1903)

Italian Serenade (1887)

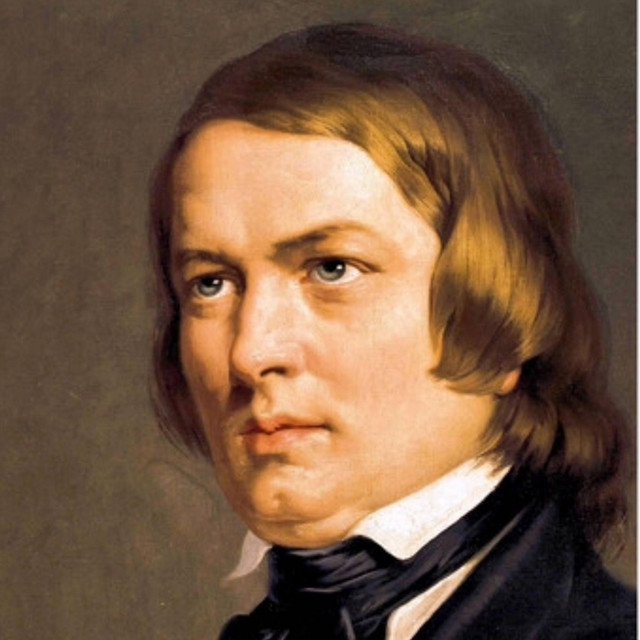

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

String Quartet Op. 41 No. 2 in F major (1842)

Allegro vivace

Andante, quasi variazoni

Scherzo. Presto

Allegro molto vivace

Serguei Prokofiev (1891–1953)

String Quartet No. 1, Op. 50 in B minor (1931)

Allegro

Andante molto - Vivace

Andante

Myroslav Skoryk (1938–2020)

Melody in a Minor (1982)

The Fernwood String Quartet

Julia Gessinger, Andreas Volmer (violin)

Marla Morgan (viola)

Jean-Marie Glazer (cello)

Program Notes

Hugo Wolf (1860-1903) - Italian Serenade (1887)

The Austrian composer Hugo Wolf was a superb song composer, bringing the late Romantic lied into the modern age and, with it, imbuing the lied with a new conciseness that was more a hallmark of Schoenberg’s Second Viennese School.

The new German lieder style that Wolf worked in was much influenced by Wagner. Songs were now expressive and dramatic, with an often-surprising chromatic sound. Out of conservatory, he taught music, but it was his musical brilliance and charm that brought him support. He succeeded, he failed, he returned home, he failed as Kapellmeister in Salzburg, he returned to Vienna – his depressions and mood swings kept him from the success he should have had.

In 1883, at Wagner’s death, Wolf felt that his idol had departed, and his depression and anger alienated as many patrons and friends as his charm attracted. He came to the attention of Franz Liszt, who urged him to start working on larger symphonic forms, and he started to work as a critic. In May 1887, he wrote his elegant Italian Serenade. A week after he completed it, his father died, and he sank into a year of lethargy.

The Italian Serenade began life as a simple Serenade in G major, but by April 1890, Wolf had changed its name. Written for string quartet, it was originally intended to be a standard 4-movement work, but because of the death of his father so shortly after completing this, it was left as a one-movement work.

A couple of literary works by Joseph Eichendorff may have influenced his ideas for this quartet piece, the first being poems that he had recently set and the second a novella about a travelling violinist who seeks his fortune abroad and at one point, hears an Italian serenade played by a small orchestra.

The work is not the Italian style of the time we might think of by composers such as Mendelssohn, The lightness is there, but, at the same time, there’s a more serious background. The main theme is supposed to have come from an old Italian melody, but really hasn’t been traced to a source.

The work was never performed in Wolf’s lifetime as he concentrated more on lieder. The work remains one of his few non-song pieces. In early 1897, Wolf’s mental state declined due to a syphilitic infection that drew him down into insanity. In his last years in the insane asylum, he tried to return to the Serenade to write other movements, but nothing resulted. The string quartet, arranged in 1892 for string orchestra, remains a lovely example of what talents Wolf had, but which were lost to his mental condition. — Maureen Buja

Robert Schumann (1810-1856) - String Quartet Op. 41 No. 2 in F major (1842)

Robert Schumann remained a diligent music student throughout his life, poring over the works of the canonical masters as well as reviewing the newest compositions for his music journal. He also tended to concentrate on specific genres at particular times. His “chamber music year,” 1842-1843, got off to a bad start, as he felt snubbed and disrespected while travelling with his wife, Clara, on her tour of northern Germany and Denmark. He abandoned the tour before it ended, returning to Leipzig alone. There, he fought depression with counterpoint exercises and studied string quartets by Mozart, Beethoven, and Haydn.

After Clara returned home at the end of April, they worked together at this study, and in June Robert began sketching a pair of his own string quartets, finishing them in early July. He had sketched some quartets several years earlier, but these were the first he completed, and a few weeks later he added a third to the set, which became his Opus 41, dedicated to his friend Felix Mendelssohn. All three were premiered as presents for Clara on her 23rd birthday, September 13.

The influence of Haydn is apparent in Schumann’s obsession with a single principal theme in the first movement of his Second String Quartet, and Haydn also often employed some of the imitative twists that Schumann uses so effectively here. For his slow movement, Schumann offers an offbeat – often literally – set of variations in A-flat major, formally rounded with the recall of the opening and an allusive coda. The athletic Scherzo is in C minor, with a funny little Trio in C major; Schumann combines these in a coda, which sets up the introduction to the whirlwind finale.

Like the finale to the First Quartet, this one consolidates and clarifies the harmonic adventures of the preceding movements with vigorous joy in the doing. — John Henken

Serguei Prokofiev (1891–1953) - String Quartet No. 1, Op. 50 in B minor (1931)

Prokofiev’s first string quartet comes shortly after the first version of his symphony no. 4, and just before the fourth piano concerto, so it seems a bit late in coming for someone who already had some quite memorable works under his belt. Maybe that helped to make his first string quartet an impressive one, but regardless of the reason, impressive it is.

It was commissioned by the Library of Congress, but it wasn’t the composer’s first chamber effort. He wrote an Overture on Hebrew Themes, op. 34 for clarinet, string quartet and piano, as well as a quintet, op 39, (oboe , clarinet, violin, viola, bass), but this is his first (and clearly most traditional) chamber effort.

It’s in three movements, coming in at about 23 minutes. Whether it’s because it came late in the composer’s career, or because of the inspiration he drew from elsewhere, I feel this work is of a rather serious nature, perhaps rigorous is a better word, and of outstandingly high quality.

As a first string quartet, it’s not a trial run; it doesn’t feel like a first. From the downbeat, there’s an engaging propulsion, an intensity, but it’s balanced with charm. I hear (or am reminded of) Ravel in this work: it has such perfectly-executed qualities in melody, rhythm, attacks, contrasts, that we as listeners can relish in such well-crafted detail, and yet they never get in the way of the pure enjoyment of the music. There is a clearly identifiable second subject, and a robust, stormy development section. There appears our opening figure for a moment, deceptively, but the music keeps developing, organically, almost maniacally, but never with quite the sharp acidity of the earlier piano works we discussed last week. The recapitulation brings us back to the opening themes, but it isn’t just a repeat of what we got earlier, showing some real change in the arc of the movement.

The second movement begins, and we think, “Ah, the slow movement.” It sounds adagio-like, richly harmonic, like a modern version of the beginning of Tchaikovsky’s serenade, and the intensity wanes a bit, but it isn’t long before the cello sparks the quartet to life and we have, not a slow movement, but the scherzo, a more mischievous-sounding movement, not diabolical, an exercise in light and shadow, playful but with a hint of sarcasm, a wonderfully rich movement that shows Prokofiev’s apparent mastery of the quartet ensemble, even though he’d never written one before. It seems perfectly idiomatic for the quartet, another engaging, truly breathtaking work, with moments of plucked strings, blasts of color and texture that are extremely effective.

The third and final movement, then, is our slow movement but also our finale, a movement of considerable emotion. I feel, in listening to the third movement, that it reveals that each of these movements is a continuation of the prior, that we’re not listening to three separate movements or expressions of a mindset, but to three interconnected parts of a whole. There’s no motivic relation or interconnectedness, but the three movements seem to be along the same trajectory, one of apparently increasing melancholy. The finale doesn’t border over into sappy sorrow, but is an expressive, heartfelt, impassioned movement, with gloom and sadness, tastefully contrasted with glimmers of sweetness.

It’s a bit of a question mark at the end of this powerful work. It presents all the intensity and fullness that you’d want from a finale, but it doesn’t answer the questions it asks, doesn’t resolve its own sorrows. By giving us a sonata-form first movement, a scherzo, and a slow movement, there’s a sense that the work is incomplete, that there should, in this layout, be a fourth, but only because of tradition, because that’s what we expect from a string quartet. In reality, the work is plenty intense and substantial enough to stand on its own, but it’s like a movie that ends without resolving the tension that had been created throughout the rest of the work, leaving you to draw your own conclusions, and this is in itself a powerful conclusion.

I wonder about the personal nature of a commission like this, what the ‘terms’ or details were surrounding the commission, because this seems like a very personal work, an expression of some inner turmoil (as cliché as that sounds), a retelling of a personal experience, a working out of certain emotions, but that can also be universal.

It’s a stunning, confident, powerful first string quartet, deceptively well-executed for a first quartet, but it also displays many of the characteristics of Prokofiev’s music, if perhaps in a more polished, subtle way. The composer loved the third movement so much he wrote a version for string orchestra that apparently still gets some attention. It’s a splendid work, and one finishes listening with not only the desire to listen again, but perhaps a bit of disappointment that this is one of only two quartets the composer wrote. (Source)

Myroslav Skoryk (1938–2020) - Melody in a Minor (1982)

Over a career that spanned more than six decades, Myroslav Skoryk (born July 13, 1938 in Lviv; died June 1, 2020 in Kyiv) made immense contributions to musical life in Ukraine. His vast compositional output includes works for orchestra, chorus, ballet, and opera; jazz and popular music; and scores for more than 40 films. He taught composition and theory at the Lviv Conservatory and the Kyiv Conservatory, and served as the Artistic Director of the National Opera of Ukraine.

While Skoryk’s compositions draw on a wide variety of stylistic influences, from Carpathian folk music to the avant-garde, his most celebrated work, the Melody in A Minor, is disarmingly simple. Written for the 1982 film High Mountain Pass, Skoryk said that he wanted this piece to convey an understanding of tragedy that cannot be expressed in words. Melody has since become one of the nation’s spiritual anthems, and we offer our performance in solidarity with the people of Ukraine.